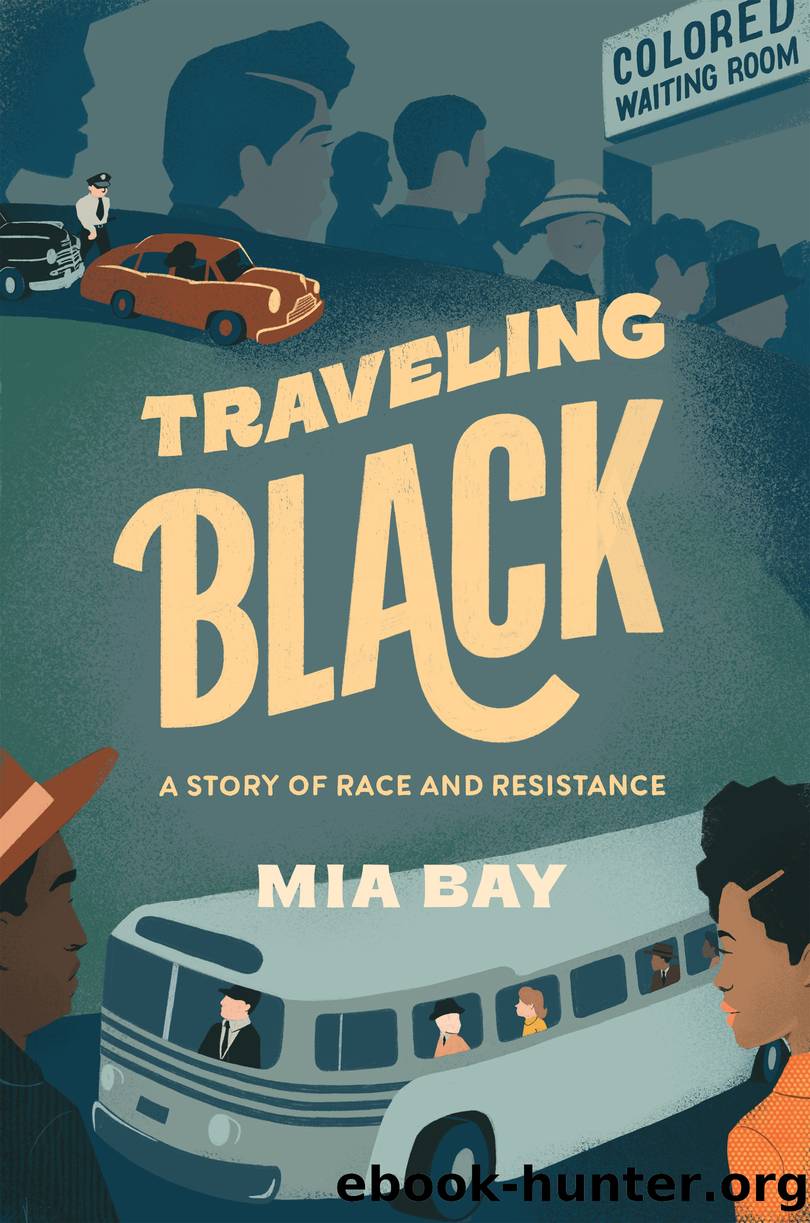

Traveling Black by Mia Bay

Author:Mia Bay

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Harvard University Press

SEGREGATING SEATING

During World War II, the travel needs of military personnelâBlack or whiteâtook priority over those of all other passengers. In these years the airlines also began to experiment with various forms of seat segregation that either confined Black passengers to certain seats, or made sure they all shared the same row. How common such practices were is difficult to determine, given that Black passengers were not numerous and the airlines made no public commitment to segregated seating. But in 1945 the Chicago and Southern Airline (one of Deltaâs precursors) admitted that it practiced Jim Crow seating on its Dixie-bound flights.

âIt is true that Negro passengers are requested to assume the forward seats on the airplane,â an official for the airline wrote to Theodore Allen, a Black federal government employee who protested when one of the airlineâs stewardesses made him reseat himself in the front of the plane, after he and the white man with whom he was traveling had taken seats in the middle of the plane. The airlineâs representative was unapologetic about the practice and suggested that âfrom the standard of personal comfort, these [forward seats] are the most desirable seats in the aircraft. Thus it should be made clear that the practice rather than one of discrimination is one of offering Negro accommodations and facilities which are equal or superior to those offered other passengers.â59

Langston Hughes was familiar with the Jim Crow forward seats, and actually agreed with this positive assessment. A well-known poet and playwright, who described himself as âhalf writer and half vagabond,â Hughes was an early and enthusiastic advocate of air travel.60 In a 1946 Chicago Defender column celebrating the advantages of âPlanes vs Trains,â he wondered why âeverybody does not travel by plane.â Faster and cleaner than trains, planes held additional advantages for âcolored travelers in the South.â âAs yet, there are no Jim Crow planes,â he also noted, before qualifying this claim by saying that he had heard that âcolored travelers in Dixie are sometimes given the No. 1 seat,â and admitting that âonce in Oklahoma I was most courteously assigned to the No. 1 seat.â But he had no objections to this seat assignment, as he was convinced that the No. 1 was âreally the best seat, being at the front with lots of leg room and a wonderful view unobstructed by the wing.â61

Not all travelers shared Hughesâs enthusiasm for the No. 1 seat. Commercial airlines in the 1940s typically used propliners, or propeller-driven planes, which were powered by propellers located in the front of the plane. These planes varied somewhat by model, but their front seats tended to be noisy. First-class seating on propliners, if available, was invariably located in the rear, which was not only quieter, but easier to enter and exitâgiven that these planes were entered through doors located on the tail of the plane. Far from being universally regarded as the best seat on the plane, the proplinersâ No. 1 seats may have struck many as the worst.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19088)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8910)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6887)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6280)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5802)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5754)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5446)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5219)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5088)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4925)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4789)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4720)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4512)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)